“There is nothing in the world like a persuasive speech to fuddle the mental apparatus and upset the convictions and debauch the emotions of an audience not practiced in the tricks and delusions of oratory.” – Brother Mark Twain, The Man That Corrupted Hadleyburg and Other Short Works

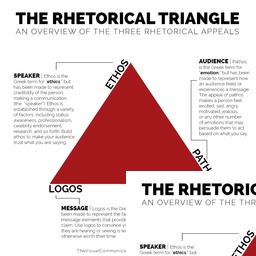

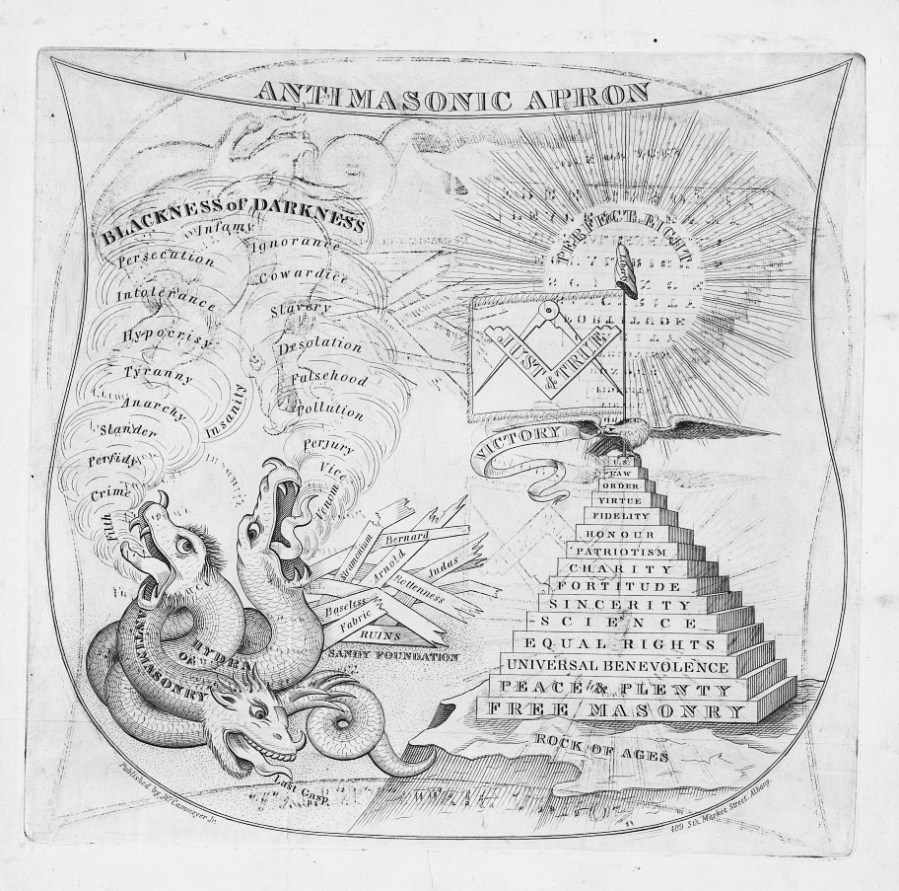

Rhetoric is the art of persuasion; or the “application of language in order to instruct…” (Wikipedia, 2020) It is one of the three arts of discourse (the other two being grammar and logic). These three items combined form what is referred to as “the trivium.” Rhetoric can, invariably be broken into three appeals:

Ethos – “ethos” is the Greek term for ethics. In this context however, it is used to represent the credibility of the speaker. The goal for the speaker is to establish ethos; that the listener(s) can trust what is being said. This can be done in a variety of ways including the speaker’s status, awareness, professionalism, celebrity, research, etc. In other words, we trust what this person says because of their experience or exposure to the issue.

Logos – “logos” is the Greek term for logic but in this context has been made to represent the facts, research, and other components of the message or speech which provide support, proof, or evidence that what is being said is true.

Pathos – “pathos” is the Greek term for emotion but in this context has been made to represent how the audience feels or experiences a message. Pathos has as much to do with what one is saying, as how it is being said. This is typically the component of rhetoric which calls a listener to action.