Have you ever wondered why our working tools exclude some common and necessary tools of the operative trade? I have. The one which springs to mind the most readily is the humble chisel. In the first degree, we learn of the importance of the twenty-four-inch gauge and the common gavel – tools which allow us to measure the work in front of us and provide a means of carrying out the task (if only partially). How, though, are we to accomplish anything without the tool with which we chip away at the rough stone?

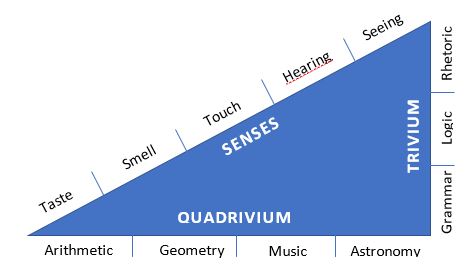

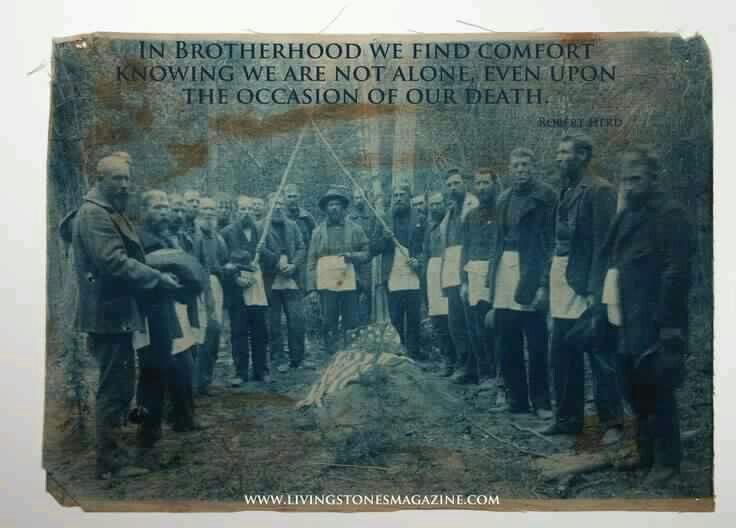

Dated to at least 8,000 BCE, chisels have been found all over the world, as have the results of their use. The term, “chisel,” is believed to have evolved from the French word, “ciseau,” meaning “to cut,” which itself may have come from the Latin word, “cisellum,” meaning the same. In operative masonry, the chisel is typically a small, handheld tool of steel or iron and is used to mark or remove unnecessary portions of the stone, leaving only what is intended to be kept behind. This, of course, is an alternative to simply hitting the stone with the gavel, resulting in a less controlled outcome. In the absence of the chisel, the symbolism could be confusing. To be clear, the chisel is part of the working tools in other jurisdictions, most notably in the UK. But why not here? In 1832, a meeting – now known as, “The Baltimore Convention” – was held in response to rising anti-Masonic sentiment caused by the notorious 1826, “Morgan Affair.” Among the many items changed at this convention was the working tools and specifically the exclusion of the chisel. It is unclear why exactly why these tools were dropped from ritual but, we can at least understand their original, speculative symbolism. The chisel, “points out to us the advantages of education, by which means alone we are rendered fit members of regularly organized society.” Which make sense, if we put it in the context of the other tools identified in the Entered Apprentice degree.