There’s a disappointingly superficial piece on the Washington Post website today by feature writer Sadie Dingfelder about the George Washington National Masonic Memorial in Alexandria, Virginia. As I read it, I was immediately struck by a picture it paints of a growing number of Americans these days and how Freemasonry is seen by them.

Here are some excerpts from Dingfelder’s article, ‘Unlock the secrets of the Freemasons – or at least gawk at their strange costumes‘:

“Is it usually pretty quiet here?” I asked the person checking me in, who later turned out to be my tour guide.

“It can get pretty busy in the summer,” he replied. In warm months, busloads of Masons visit the memorial, he said.

“I must admit, I don’t know much about Freemasons,” I said, which prompted my guide to launch into a short history of the group.

“It’s basically a fraternal organization,” he concluded. “They do a lot of service and charity work.”

“Oh, so it’s like the Rotary Club, but with costumes and secret handshakes,” I said…

[snip]

The memorial also houses a museum of Masonic history, and we’d just arrived on a floor devoted to that when a muffled voice emanated from my guide’s walkie-talkie. He rushed off to fetch a late-arriving tourist, leaving me alone in a room full of creepy mannequins attired in the costumes of various Freemason subgroups and affiliated societies, including Shriners’ fezzes, Arabic-looking turbans, militaristic uniforms and one costume with a jeweled breastplate, an imitation of vestments worn by ancient Israelite priests.

I found this to be a fascinating glimpse into a less-woke era, but I was disappointed that I couldn’t find any explanatory text about why these groups of (I imagine) white men wore Middle Eastern-ish garb, and whether similar costumes are still used today.

|

Some of the Freemason costumes on display struck this reviewer as Orientalist,

militaristic or just plain strange. |

Scattered around the mannequins were displays of random club ephemera — plus a few inexplicable objects, including a jaunty bobblehead doll of the controversial Christian figure Jacques de Molay, a monk who fought in the Crusades and was later sentenced to death. De Molay’s medieval order, the Knights Templar, inspired the modern-day Knights Templar — a Christian-focused subgroup of Freemasons, my guide explained after returning with a mysterious man in a trench coat…

[snip]

If I’m right, he’s an increasingly rare breed. Freemason membership has been in decline since the 1960s, according to a chart on display in the museum’s basement. “Civic life declined as people spent more time alone in front of a television or computer screen,” the accompanying text explains. Fair enough, but I’m betting that the Masons’ fraught racial history and continued exclusion of women have also contributed to their diminishing relevance.

I mention this because the Masonic memorial may be on its way to becoming just that: a memorial to a bygone organization, where powerful men once gathered to socialize, plan charitable work and wear Orientalist costumes. Perhaps a lot of this is best left in the past, but it seems to me — a person who spends way too much time alone, in front of a computer — that there’s something here worth bringing into the future.

The benefit of resources like LinkedIn is that you can go and find out about the background of people whom you otherwise don’t know at all, and Sadie’s profile yields a few items worth noting. She’s not a teenager or a college student — she graduated in 2001, so she’s in her mid- or even late-30s. Sadie’s a graduate of Smith College (a private liberal arts college for women only in their undergrad program), and she’s been working as a writer for the Post in the Washington D.C. area in various capacities for ten years. She lives and works in the very city that a lot of Masons (and even non-Masons) regard as one heavily influenced by Freemasons from the past, and (if you believe in such things) filled with Masonic symbolism even in the street map. TV producers of programs about Freemasonry are obsessed with the idea. So it surprised me a bit to see just how little knowledge or awareness of Freemasonry she seemed to have when she walked into the Memorial — and apparently, how little she had actually learned by the time she left. After touring the place, she declared that Freemasonry is little more than a bygone organization.

This isn’t a hit on Ms. Dingfelder, not at all. It’s a comment on how diminished we have become in the collective American psyche. I thought we had reached rock bottom in that regard back before novelist Dan Brown put Freemasonry back on the map in the early 2000s. Since those dark days, cable television has had loads of programs about Masonry. Stacks of factual, intelligent, and truthful books (including mine and Brent Morris’) got poured onto the market. Freemasonry worked its way into pop culture references like movies, music and TV shows. I had thought we had even turned a tiny corner and tipped the scales slightly back into our favor, at least as far as a basic awareness of Freemasonry was concerned.

Indeed, the Scottish Rite NMJ did a survey two years ago and discovered that a full 81% of respondents had at least heard of Freemasonry, even if they didn’t know what it was. But as I think back over the last five or six years now, and reflect on my own contacts with the public about it, I fear more people are even less aware of what Freemasonry actually is than in the 1990s. In that same survey, less than 30% actually knew what the values of Freemasonry were. And the most common question I get asked by non-Masons under 35 these days once I get my basic elevator speech out of the way is, “But just what is it that you guys DO? What’s the point?”

That shouldn’t be a shock, since we are about one generation removed from the 1990s. The adults in 1990 were having children at that moment in time, and we are now encountering those former infants as adults today. Already by 1990, Freemasonry had been waning, along with a raft of other social changes taking place then. By 1990, the fraternity was already down in membership by more than 30% from its 1958 height. It was blatant that the Baby Boomers had steered clear of Freemasonry, just as they had so many other so-called “Establishment” ideals of their parents. Organized religious attendance was decreasing. Divorce rates had skyrocketed. Childbirths were down substantially, and most concerning, single parent households (usually single moms) were taking a major upswing. It was into this period that today’s current Millennial adults now in their late-20s and 30s were born.

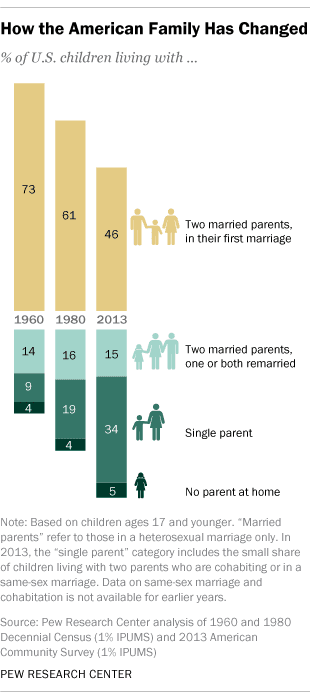

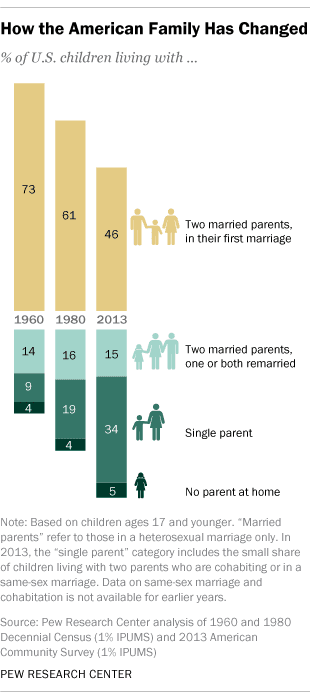

According to the Pew Research Center, fewer than half (46%) of American kids under 18 years of age are living in a home in 2018 with two married heterosexual parents in their first marriage – what is quaintly called a traditional family household. This is a huge change from 1960, when 73% of children fit this description, and 1980 when 61% did. At less than 50% today, it’s certainly a dwindling tradition.

One of the most enormous shifts in family structure is this one: 34% of American children today are living with an unmarried parent—up from just 9% in 1960, and 19% in 1980. In most cases, these unmarried parents are single, without a live-in partner of any kind to help raise and educate the children.

When I wrote Freemasons For Dummies in 2004, there was still a reasonable chance that enough grandfathers had been Freemasons in sufficient numbers that their grandchildren had at least encountered the fraternity in their lives. But that percentage has done nothing but drop since then.

Fewer children today have full-time fathers than ever before in recorded history, and even fewer of them have a grandfather to pass along older traditions like Freemasonry and numerous other important values.

(Interestingly, 5% of children are not living with either parent at all. In most of these cases, they are living with a grandparent—a phenomenon that has become much more prevalent since the recent economic recession.)

When you take into consideration all of this stew of statistics, it’s clear that Freemasonry as a subject for observation by children has a pretty paltry chance of being passed along to the current and future generations by many fathers, grandfathers, siblings, uncles or other influential men in their lives.

In other words, there’s no statistically significant reason why Sadie Dingfelder would have encountered Freemasons in her family. She doesn’t mention any sort of family connection to the fraternity, so the only way she knows anything at all about us is from what she picked up by cultural references she has encountered as a teenager and adult. Like going to the Memorial, poking around on the Internet, or catching a rerun on A&E or the History Channel. I suspect she may not have a single family member, friend or acquaintance who is a Mason, or was in recent memory.

Mull that over. And if she has children of her own today, what chance will they have as adults to inherit any sort of collective, cultural knowledge of Masonry in another 20 years?

Note her comments about Masonry being from a “less-woke era” (a colossally imbecilic adjective if ever there was one) and her pronouncement that our “fraught racial history and continued exclusion of women have also contributed to their diminishing relevance.” Whether you believe that or not, that is one narrative being circulated about us today in this hyper-heightened period of describing every single subject on the face of the Earth in terms of gender, race, offense, privilege and oppression. Young people are being taught a dramatically different (and arguably damaging) version of Western and American history now than older generations, and the values, traditions and institutions of the Founders and prior important historical figures are being derided or ignored altogether. The images of George Washington and Ben Franklin as Freemasons don’t carry the sort of influence and impact they had even 20 years ago – some today would even argue that they are a negative. And let’s not even venture into the demographics regarding religious beliefs among Americans in 2018, or how religious Americans are almost uniformly portrayed in a negative light by the pop culture.

None of this is an indictment of anyone, because there’s no single villain we can isolate and counter, argue with, or shoot out behind the barn. These are simply the current circumstances we find ourselves struggling in. That’s what we’re facing going forward as we try to craft messages for the profane world, design our museums, and sit for interviews with the press. Once again, the culture has shifted under our feet, and this time, we find ourselves potentially tap-dancing on a minefield.

As bleak as all of this may seem, at its core, Freemasonry is and will remain important and relevant and needed as time marches on, but it’s up to each of us to do our part to ensure its future by not hiding what’s left of our light under a bushel and permitting ourselves to be ignored to death. Remember that even Sadie recognizes this, and concluded her essay with this thought: “Perhaps a lot of this is best left in the past, but it seems to me — a person who spends way too much time alone, in front of a computer — that there’s something here worth bringing into the future.”

There is indeed.

This article was reblogged from: https://freemasonsfordummies.blogspot.com/2018/11/freemasonry-in-age-of-woke.html?m=1